A (Not Always) Open Door Policy

Published June 2018

A caring and supportive relationship with members of our team is the foundation for all we do as leaders and managers. Everything is easier, and more effective, when mutual trust exists and employees know that we have their best interests at heart.

Intentionally and regularly spending time with each employee in their work area (i.e., rounding) is a proven technique for deepening the relationship and for promoting frequent, constructive dialogue about the business. When employees know that a regularly scheduled visit is upcoming, they’re more apt to table topics until then, making more effective use of both parties’ valuable time.

Nonetheless, it’s still important to be available to employees when they need to talk. Managers often brag about their “open door policy.” Does this mean that one has to always be available?

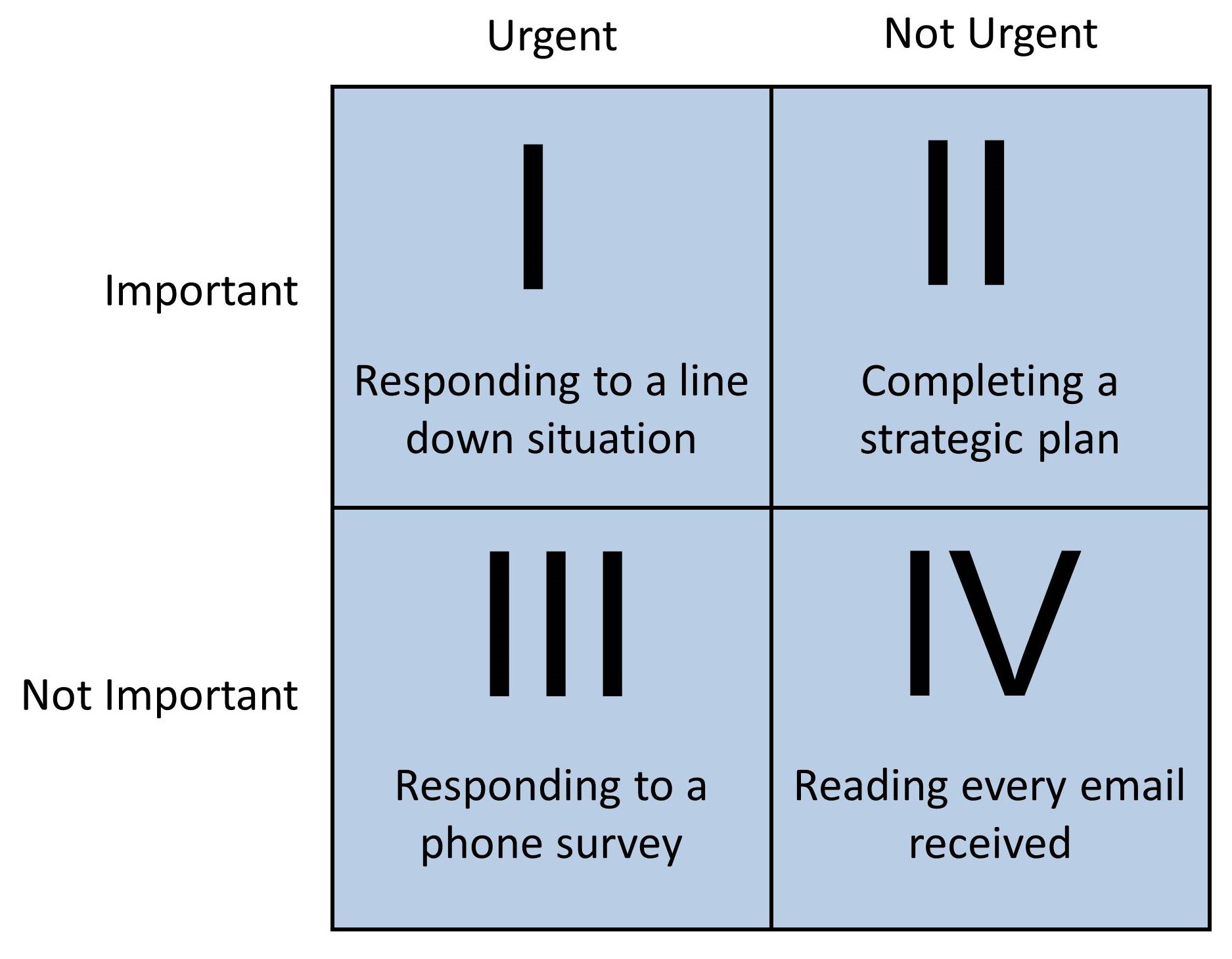

To answer, let’s revisit Stephen Covey’s third of seven habits of highly effective people—put first things first. Covey explains that the demands for our time can be classified by two factors, importance and urgency. He places the demands for our time into four different quadrants:

We want importance and not urgency to be the primary driver of how we spend our time. But urgency possesses an alluring siren call, frequently suckering us to believe a demand is also important (Quadrant I) when it is really just urgent (Quadrant III).

Proactively scheduling important but not urgent tasks (Quadrant II) is a proven strategy for ensuring that one’s day isn’t consumed by the urgent but trivial (Quadrant III). It dramatically increases the odds that we will follow through on our goals to round on employees and to complete that critical project on time with quality thought instead of cramming the night before.

Therefore, there are occasions when the best use of a leader’s time is to be dedicated to a critical, scheduled Quadrant II activity, and essentially off-limits to the team. One can use the daily huddle to announce that they will be working on a critical project between 9-11 am and that they appreciate the team respecting that time.

My friend Roger has developed a simple, visual system with his team:

- When the lights are off and the door is closed, it means that he’s out of the office.

- When the lights are on and the door is open, it means that he’s in and available.

- When the lights are on and the door is closed, it means that he’s in, but working on an important task (what Covey called a “big rock”) and prefers not to be interrupted.

Team members should understand that a true emergency (i.e., important and urgent) warrants an interruption. But someone stopping by to announce that there are free donuts in Marketing probably justifies a short coaching opportunity. (There are always free donuts in Marketing; free donuts in Accounting … now that’s news!)

Obviously, any manager spending a majority of their time behind a closed door is evading a critical portion of their job. But being available to employees—outside of an emergency—doesn’t have to be a 24/7 proposition. Intentionally carving out designated time to work on important projects, and protecting that time against interruptions, results in higher quality work and a saner manager. It can also lead to more independent employees who don’t feel compelled to run every little thing by the boss.

—

Back to the Working Great! archivesView the PDF version:

Check out the Working Great! archives for columns on other pertinent business issues

Copyright 2018 Brimeyer LLC. All Rights Reserved.